The voice of ink and rage

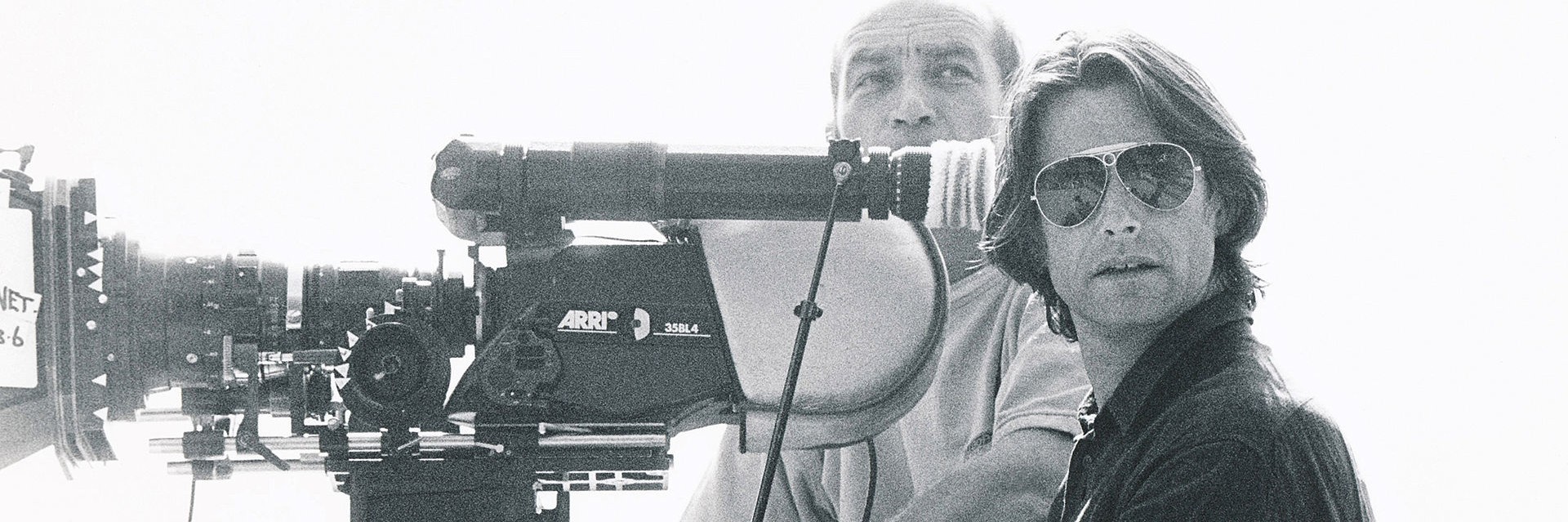

Retrospective Bruce Robinson

»I got no voice. I don't know how to write like myself«. Around this very statement circles »The Rum Diary«, Bruce Robinson's cinematic version of Hunter S. Thompson's novel. Its protagonist, Paul Kemp, has not found his voice yet. He's got the style, but not enough substance to infuse his writing with an urgency and force. And that's why he drifts from one glass of rum to the next, from one story to another. At the end of his turbulent sojourn in San Juan, Puerto Rico's capital, the journalist – played by Johnny Depp – will have finally found his voice. In the former printing shop of the newspaper where he had found a job, but not a future, he asks loudly: »Do you smell it? It's the smell of bastards. It's also the smell of truth.” And this connection is not just important for Kemp, a clear self-portrait of the wrathful Hunter S. Thompsons. Bruce Robinson is also looking for it. Constantly.

»I have no voice. I'm not sure how I should write anything.« Yes, Bruce Robinson, born 1946 in Kent County, knows self-doubt as well. Because he knows how to write about these existentialistic crises like no other screenwriter, capturing their drama as well as their ridiculousness. But his collected works make it

somewhat impossible to cast him as a Paul Kemp or even a Withnail. Even the knowledge of the autobiographic core of his directing debut »Withnail & I« does not change that. Even as an actor, working with Franco Zeffirelli in »Romeo & Juliet« and Ken Russell in »The Music Lovers«, François Truffaut in »L'histoire d'Adèle H.« and Carlo Lizzani in »Kleinhoff Hotel«, he was somewhat of an auteur du cinema. His characters are part of the films' artistic concept, but also unmistakably creatures of Robinson's creation. He makes them his own and therefore expands his directors' vision. Which is why it could be only a matter of time until he started writing screenplays and direction himself.

Especially his portrait of a paranoid and desperate German terrorist in Lizzani's wild thriller from the leaden times of the late 70s looks like a first template for his upcoming screenplays. The left-extremist Karl, hiding in a hotel room, always moves between wild excesses of violence and paralyzing despair. Death already has him within its unyielding grasp, but Robinson plays his part with manically energy. Karl's anger is not unlike Withnail's and Kemp's rage; even his longings and self-revulsion can be found in both characters. Like both artistic revolutionaries he is fighting a society defined by indifference and greed. But like a madman attacking a concrete wall, he has lost all sense of proportion.

A sense exorbitance is certainly part of Robinson's work, too. Films like »Withnail & I«, this venomous swan song to the great expectations and lofty illusions of the 60s, »How to Get Ahead in Advertising«, his prophetic reckoning with humanity's never-ending greed, have a terrific explosive force. Like, Karl, he attacks the status quo of a society bent on destroying each individual. But his weapon is his art. Both films' sarcastic wit is a shot right through the heart of our longings and the trite lies we use to justify our own indifference and egotism. But he doesn't seem to have high hopes for art ever changing anything. Not really. It is like Kemp's remark about American tourists in Puerto Rico: »The great whites. Probably the most dangerous creatures on earth.« And they are not just dangerous, but practically unstoppable.

Instead, society stops or at least hinders artists like Robinson. His radicalism made him, along the lines of great satirical moralists in other fields, like William Makepeace Thackeray and Oscar Wilde, one of the great outsiders of contemporary cinema. He did get an Academy Award Nomination for his screenplay to Roland Joffé's »The Killing Fields«, which – in its strongest moments – shows the dark side of the typically western involvement of New York Times reporter Sydney Schanberg in a foreign war. But even that was not enough to keep Hollywood's doors open in perpetuity. »Jennifer 8«, his only studio movie, certainly ranks high above the wave of psycho-thrillers about helpless women and sadistic killers the flooded cinemas in the 90s. But the compromises that the studios forced Robinson to make are clearly apparent. Sure, there are some similarities between Andy Garcia' cop who gets into the sights of his own colleagues, to the other protagonists. But the freedom that Robinson's uncomfortable view of the world and the people in it demands, Hollywood did not approve of. Which is why he increasingly turned towards writing novels and non-fiction since the 1990s.

»The Rum Diary« shows how much cinema has lost. Unlike »Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas«, Terry Gilliam's incredibly excessive cinematic version of Hunter S. Thompson's most famous book, Robinson's adaptation congenially captures the spirit of the great writer's work. Humor and anger combine inimitably, allowing him to bury the American Dream and at the same time letting us dream of another kind of cinema and another world.