The Revolutionary Retrospective

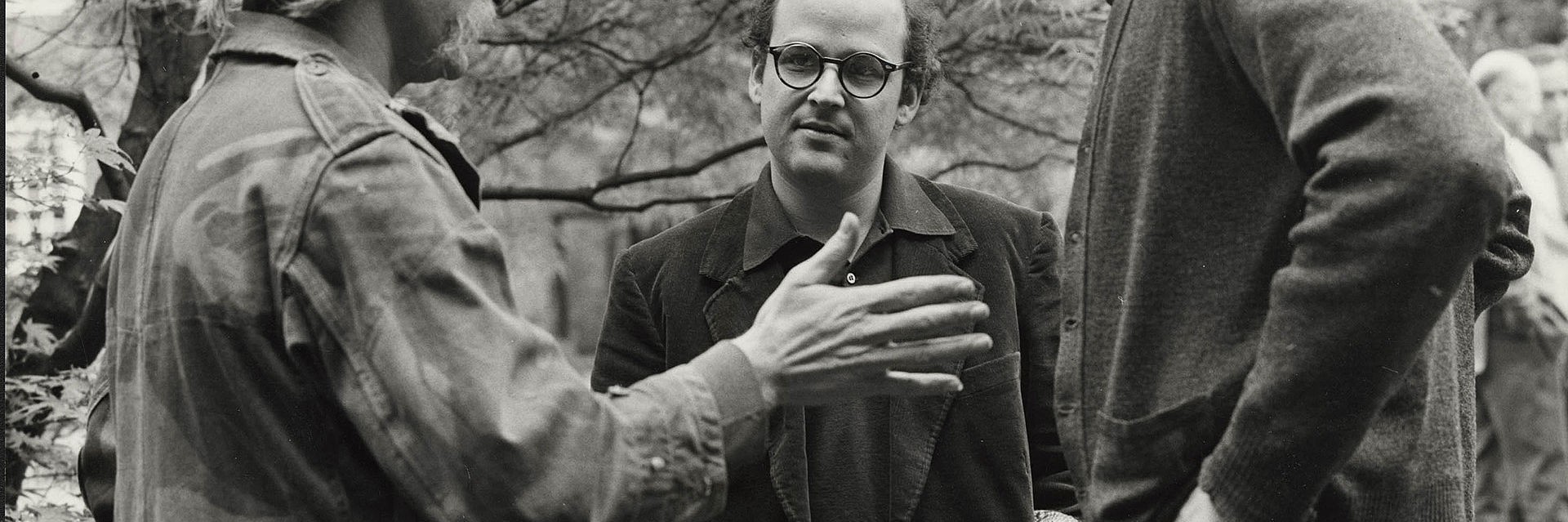

A Tribute to Edward R. Pressman

»Maverick«, that’s one of those terms film critics like to use when talking about directors who buck the conventions of the industry. The term connotes a nearly mythical ideal: the filmmaker as an artist, doing things his way and implementing his vision without compromise. A producer, on the other hand, is rarely called a maverick, since many cinephiles see him on the other side of the divide. In this tension between art and commerce, he is usually cast as the antagonist.

Still, an interview with Edward R. Pressman that appeared in the Australian film magazine “Cinema Papers” in 1989 was entitled »Hollywood Maverick«. And it would be hard to find a better description for Pressman’s position in the dream factory and in more recent film history. Because among the producers who put their mark on the American cinema of the last 50 years, the son of a toymaker – born in 1943 – really is a loner and an outsider.

Since his debut as a producer with the short film »Girl« in 1967, Edward R. Pressman has allowed more than 80 films to see – and be seen on – the silver screen. Small independent films as well as elaborate cinematic versions of graphic novels, the works of European auteurs as well as American Pulp Cinema. Modern classics like Terrence Malick‘s legendary debut »Badlands« and Abel Ferrara‘s epic cop movie »Bad Lieutenant« stand side by side in his filmography with experiments like Alex Cox’ agit-pop-masterpiece »Walker« and Mark Frost‘s southern noir »Storyville«.

Look at them fleetingly and they do not seem to have much in common. But don’t let your eyes deceive you, because closer inspection will reveal a red thread through Pressman’s career which connects the directors of his films quite strongly. From the beginning, his collaboration with Paul Williams on »Girl« and three subsequent feature films, Pressman was a discoverer and patron of directors with a rather individual perspective.

Brian De Palma and Terrence Malick, Oliver Stone and John Milius, Kathryn Bigelow and Mary Harron, Abel Ferrara and James Toback, Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Barbet Schroeder are all, in their own way, mavericks. Radical loners whose works tested the limits of cinema and continuously pushed the envelope. Films like De Palma‘s satirical rock opera »Phantom of the Paradise« and Fassbinder‘s grand Nabokovian cabinet-of-mirrors »Despair«, »Bad Lieutenant« and »The Blackout«, Ferrara‘s trips into the deepest depths of the human soul, are not only solely their creator’s masterpieces. They speak as well of Ed Pressman’s keen sense of extraordinary artists and subversive projects, His works transcend the often evoked conflict between art and commerce.

Pressman’s productions – and this goes especially for genre-fare like Milius’ stylistically visionary pulp fiction »Conan the Barbarian« and Steven E. de Souza’s underrated videogame adaptation – speak with the firm conviction that art and commerce do not have to be antagonists. Quite the contrary: they can be perfect partners, two sides of a coin. In the interview with »Cinema Papers«, Pressman clearly emphasized that a real collaboration between producers and directors cannot be reduced to a simplistic separation between creative and economic considerations. And this credo shows in each and every one of his films. »Badlands« and Oliver Stone‘s American nightmare »Talk Radio«, »Reversal of Fortune«, Barbet Schroeder‘s elegant essay about truth and its nuances, Mary Harron‘s »American Psycho«, a venomous grotesque about the inner emptiness of western society. They all make you dream. That’s what cinema can also be: uncomfortable and honest, political and poetic, experimental and intoxicating.

We connect the big advances and upheavals of the last 50 years in cinema mostly with the names of directors who have pushed and advanced the medium. Which is how filmmakers like Brian De Palma and Robert Altman, Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola have nearly become synonymous with the New Hollywood revolution of the 70s. And when it comes to the American Independents who started reinventing cinema starting from the Mid-1980s, we immediately think of Steven Soderbergh, the Coen-Brothers, Jim Jarmusch and Abel Ferrara. Pressman‘s sustained influence on both movements is often overlooked. Even though he is one of the very few producers who consistently created trends instead of following them.